|

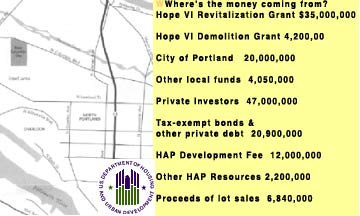

The Housing Authority of Portland will spend $152 million transforming Columbia Villa into a “mixed economy” development. Will public housing residents there really benefit from this Hope VI project?

The low-slung buildings were put up during the height of World War II to house the flood of workers pouring into Portland’s expanding shipyards. The multi-unit buildings were intended to last ten years. Sixty years later, these same buildings, spread out along meandering streets and broad greenways, constitute the city’s largest public housing project —Columbia Villa — serving as home to over 460 of Portland’s poorest families.

Now the Housing Authority of Portland (HAP) wants to tap into a federal program for “distressed public housing” to construct a new type of development at Columbia Villa. But some community critics of the proposal are wary of the federal “Hope VI” program and the way HAP intends to use Hope VI funds. They point to Hope VI’s poor national track record and believe the proposed Hope VI “New Columbia” plan will displace another poor Portland neighborhood and replace it with a boutique development where the needs of the poor will not be met.

Hope VI and the mixed economy credo In 1989, as part of the Department of Housing

and Urban Development Reform Act, Congress created the National Commission

on Severely Distressed Public Housing, an independent body charged with assessing

the condition of the nation’s public housing system and developing recommendations

for solving problems of “severely distressed public housing.” After

three years of examining the nation’s public housing stock, the Commission

found that the system was largely in good shape. Only six percent, or about

86,000 public housing units, were found to be “severely distressed.”

The meaning of that term will subsequently have a dramatic impact on the Hope VI program. However, at the time of the Commission’s report, public housing in that category had either physical or social problems which could not be addressed by most renovation programs. In particular, the older “high-rise” public tenements that were physically crumbling and creating social isolation of the poor appeared to be what was in the minds of the Commission members when they issued their National Action Plan addressing the needs of “residents, physical conditions, and management needs of severely distressed public housing developments through a variety of means.”

The following year, Congress responded to the plan with the creation of the Urban Revitalization Demonstration program — later to become known as Hope VI — as part of the Department of Veterans Affairs and Housing and Urban Development and Independent Agencies Appropriates Act of 1993. The multi-billion dollar federal grant program for redevelopment of severely distressed public housing would be administered by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). Public housing authorities — state and local entities administering federal housing programs — could apply for grants that would be issued on a competitive basis. Since 1993, $4.5 billion in redevelopment grants have been awarded, including $39 million for the Hope VI “New Columbia” project in northeast Portland.

The rise of Hope VI coincided with a new concept that was gaining popularity among public housing policymakers and others — “mixed income redevelopment” or “income mixing.” Advocates of income mixing looked at the experiences of the past, where poverty was concentrated either through economic forces (e.g. old-style tenements) or as a result of public policy (e.g. large public housing projects) and drew a number of conclusions about why both created similar sets of problems. They concluded that concentration created environments in which the poor were offered no role models to emulate and thereby break the cycle of behavior that lead to poverty. The lack of such “social capital” also meant that housing developments remained just that rather than real communities composed of some if not all the classes found in communities elsewhere. The economic vitality that came from real neighborhoods was escaping these concentrations and leaving the poor without the same opportunities for self-sufficiency enjoyed by residents in functioning neighborhoods. At a more pragmatic level, advocates saw a “rising tide lifts all boats” effect with income mixing. More affluent residents would bring with them more public and private services that would then become available to the poor. There would also be less opportunity for agencies to short-change poor neighborhoods to better meet middle class needs since both classes would be residing in the same location.

|

A reform agenda for

Hope VI

• HUD should be required to publish an updated list of public housing development eligible for Hope VI funds according to a new definition of “severe distress” created in collaboration with public housing residents, housing advocates, housing experts, and others. • All public housing units subject to demolition or redevelopment under Hope VI should be replaced with new public housing units on a one-for-one basis. • HUD should be required to issue regulations governing the admininstration of Hope VI redevelopment activities,which should provide enforceable, on-going rights of residents participation. • Public housing residents should be guaranteed the right to occupy units redeveloping under Hope VI and the relocation rights of displaced residents should be strengthened and clarified. • HUD should be required to make Hope VI program documents — including approved applications, revitalization plans, financial documents and progress reports — publicly available on its website. —National Housing Law Project |

All of this was highly theoretical with no concrete evidence that income mixing produced the desired results. In fact, a 1997 report by Alex Schwartz and Kian Tajbakhsh published by HUD — “Deconcentration: What Do We Mean? What Do We Want?” — found income mixing’s “effectiveness remains open to question” and that until the hard evidence lacking so far had been produced, “advocacy of mixed-income housing will be based largely on faith…” Susan J. Popkin, writing for the Fannie Mae Foundation (a non-profit group working to develop affordable housing and communities), called such concepts of community development “deeply flawed [with] little empirical or theoretical support.” Another Fannie Mae Foundation researcher, James DeFilippis, pointed out the fallacy of bringing in more affluent residents that offer the poor access to social networks they currently lack. The very purpose of social networking is to advance ahead of others, including your neighbors, DeFil-lipis asserts. Sharing with the poor would be acting against self-interest.

The criticism is not limited to the narrow circle of public housing experts. For many within the progressive movement, the assumptions behind income mixing reflect conservative rhetoric of the likes of William Bennet and fellow travelers that place responsibility for the plight of the poor on the poor themselves. Character flaws or lack of moral fiber, rather than economic forces and inequitable public policies lead the poor down their tragic path unless provided leadership from a responsible middle class. Such assumptions served as the intellectual underpinnings for the existence of vagrancy laws, work houses and debtors prisons in a earlier century and drive the current round draconian “reforms” of our social safety net.

Unfortunately, HUD and the Hope VI program remains wedded to income mixing ideology. When combined with the manner in which HUD administers Hope VI grants, the program produces results far different from what was in the minds of lawmakers and should raise serious questions about how Portland’s own Hope VI project will turn out.

HUD and the search for a new mission

Open nearly any HUD publication about Hope VI and you will find images of smiling poor people standing outside new, cheery-looking apartment buildings. The accompanying text will most likely leave you with the idea that most of these folks have just escaped from dark public high-rises where poverty and crime rule to a new life in their Hope VI-funded homes. It makes a nice story but bears little resemblance to what HUD has been accomplishing through the program. Rather than replacing severely distressed public housing stock, HUD has actually decreased the amount of public housing available through its administration of Hope VI.

From nearly the beginning of the program, HUD began moving away from Hope VI’s mission. In 1998, the General Accounting Office and HUD’s own Office of Inspector General found that the department had shifted towards “smaller sites with greater potential to attract private investment.” Out of 34 grants awarded in the program’s first three annual grant cycles, only seven were to replace distressed high-rise developments. HUD, contrary to the impression made by its own literature, admits this shift exists and that the department cannot guarantee it will deal with the 86,000 units identified by the Commission or that doing so was the real

|

A Hope VI

“New Columbia” Timeline 2000 2001 June 2002 Nov. 2002 Dec. 2002 Jan. 2003 •Preliminary Plat submitted to City •Development of final plat design begins •Design and engineering of streets, utilities and buildings begins April 2003 Sept. 2003 Oct. 2003 Dec. 2003 March 2004 April 2004 Feb. 2005 May 2005 Dec 2006 |

HUD continues to ignore Congress’s and the public’s intent through the way it administers the Hope VI program. In most cases, when Congress enacts a new program, the responsible agency develops policies, procedures and administrative rules that translate Congressional intent into tangible action. In the case of Hope VI, HUD has avoided doing this whenever possible. As a grant program, Hope VI already relieves HUD of some of the details that would be necessary if the department was actually carrying out the revitalization projects itself. The grant process, furthermore, has been used to argue for less regulation rather than more so as to avoid excluding creative new approaches to the problem. This includes creating criteria for determining what constitutes “severely distressed public housing” and establishing uniform rules for HUD and the entities receiving Hope VI grants for public hearings and input.

One of the “creative approaches” HUD wants to keep in the mix is the creation of public sector-private sector projects. Advanced as key to leveraging more money into public housing revitalization, the public-private strategy serves to promote the income mixing strategy that HUD has taken to heart. The mix most favored is one-third public housing, one-third tax credit or other subsidized housing, and one-third market rate rental or homeownership housing. HUD encourages grant applicants to seek out mixed income development plans even if it means reducing the number of existing public housing units rather than pursue straightforward one-for-one replacement. In the case of the Miami-Dade Housing Authority’s Scott Homes development, several applications were filed with HUD, each one calling for greater reduction in the public housing element to make room for subsidized or market rate housing. The final application approved by HUD in 1999 called for the elimination of 770 units of “conventional rental public housing in two sites.”

The Scott development is no anomaly. HUD’s encouragement of local housing authorities to make room for private-sector participants in Hope VI projects has resulted in a significant reduction in public housing — housing for the most needy of our population. Through Hope VI, HUD has approved the demolition of 70,000 public housing units. With the reduced replacement rate encouraged by HUD, and the additional loss of public hous

ing units through non-Hope VI programs, the net loss could be as high as 107,000 public housing units demolished.

This reduction comes at a time when the lowest income families are most in need. In testimony before Congress in 2001, HUD reported that the total rental housing stock for the nation increased by about 725,000 units from 1991 to 1999. These units were largely affordable for low income families at or below 80 percent of the area median. Those households with the lowest incomes faced different circumstances. For every 100 low income renter households in 1999 only 40 affordable units existed.

HUD continues to insist that these temporary shortages are worth being able to replace housing projects with real communities where “social capital” will transform all living there. What the department refuses to admit is that their policy ignores the value of public housing as a much-needed resource. As the National Housing Law Project observes in its 2002 report “False Hope,” exposing the poor to “social capital” could occur without the loss of public housing stock by creating new housing within more affluent neighborhoods where the moral examples and networking opportunities deemed so important by income mixing advocates already exist. Another option would be direct investment in the services and other opportunities that income mixing is meant to create indirectly through the introduction of more affluent residents. These methods, furthermore, would stop the practice of making our poorest citizens pay — through loss of housing — for a transfer of public wealth to the private sector in the name of an unproved theory.

The rocky road Hope VI has traveled has not dimmed enthusiasm for the plan — at least among cash-strapped housing authorities. That is certainly a major factor in the Portland Housing Authority’s (HAP) decision to go after Hope VI dollars.

HAP Executive Director Steve Rudman admits after a New Columbia open house presentation that if adequate funds were available from other programs for a revitalization program of this size, he would be just as happy pursuing funding that way. But, as he points out, Hope VI is one of the few programs that allows agencies like his, who have their hands full, to leverage the grants into significantly larger sums.

There’s no question HAP has its hands full. Each year the agency provides rent assistance to over 5,600 renters, most to extremely low-income households renting privately owned units. HAP also maintains and operates 2,800 units of public housing in Multnomah County, including north Portland’s Columbia Villa. Over the past four years the agency has spent over $119 million on rent assistance and more than $30 million on the construction or preservation of public housing units. The 2,800 units of public housing cost HAP another $19 million. A depressed economy, gentrification and aging infrastructure means HAP is facing growing numbers in need of help just as funding becomes tighter.

Columbia Villa, home to 1,300 Portlanders living in 462 units, is HAP’s oldest public housing facility. Built in 1942 with a life expectancy of ten years, the housing and supporting infrastructure, now 60 years old, is becoming a financial drain on the agency. Over the past several years HAP has put millions of dollars into dealing with lead contamination, faulty water lines and a collapsing sewer system. Conditions are further aggravated by a street system that is largely disconnected from the surrounding street grid, and the absence of nearby retailers. There’s little question that the physical structures of Columbia Villa fit the definition of severely distressed.

In late 2000, HAP submitted an application for a Hope VI grant proposing a mixed income development favored by HUD. The application proposes to reduce poverty concentration in the area by reducing the number of public housing units from 462 to 370. HAP has committed to no net loss of public housing within the city and has told Columbia Villa residents that the 92 units cut from the project will be replaced off-site in another part of the city. In addition to the new 370 public housing units to be built, a mix of low- and moderate-income affordable housing and market rate housing will be created on site.

But money in amounts not available elsewhere and commitments by HAP to avoid the pitfalls of other Hope VI programs still beg the bigger question of the mixed economy foundation for New Columbia and all the other Hope VI projects. Does it make sense to attain short-term funding goals if the long-term strategy is fatally flawed? Is New Columbia the best use of scarce federal housing dollars if in the end we end up with fewer resources for the most needy Portlanders and another boutique neighborhood that will eventually displace even more low-income people?

These aren’t the only problems facing the Hope VI program and more specifically the Hope VI New Columbia project. As we’ll see in the next installment of this story, HUD’s track record on relocating public housing residents has been less than stellar, and HAP’s confidence that they can do better deserves far more scrutiny than it is currently receiving, particularly in light of the compressed timeline.

Dave Mazza is the editor of The Portland Alliance.

|

The Portland Alliance

2807 SE Stark Portland,OR 97214 Last Updated: December 30, 2001 |